China’s EV brands are conquering the UK market faster than Japan did in the 1970s. How BYD, MG, and others are reshaping British motoring through technology, pricing, and perfect timing.

How China’s U.K. EV Assault Surpasses Japan’s Seventies Invasion.

There’s a familiar tremor running through the British motor trade. A certain déjà vu. The showroom floors, now electrified with pixel-heavy infotainment and suede-trimmed crossovers bearing names like BYD, Omoda and Jaecoo, are humming not just with battery current – but with history. We’ve seen this play out before. Back in the oil-slicked, strike-riddled 1970s, when Japanese badges like Datsun and Toyota crept into British driveways while the unions down at Cowley and Longbridge were still arguing over tea breaks.

But here’s the kicker: this isn’t just a rerun with better batteries. It’s something bigger, bolder, and infinitely faster.

Let’s rewind to the early 1960s. Britain was still clinging to its imperial swagger, and its car industry was a global heavyweight. We were second only to the Americans in output, churning out Cortinas, Minxes and Victors at a blistering pace. But beneath the bonnet lay a wheezing, smoke-belching machine that hadn’t seen a proper rebuild in decades. Chronic underinvestment, fractious management, and mass walkouts meant the rot was deep-set long before anyone uttered the word “Datsun”.

By the close of that decade, Japan had quietly overtaken us, not with muscle cars or motoring romance, but with small, efficient, no-nonsense machines that started every morning and didn’t eat their own gearboxes. British Leyland, our great white hope, was a bureaucratic Frankenstein built to paper over the cracks. The Japanese, meanwhile, had mastered kaizen, built factories that ran like Swiss watches, and tapped into a global shift toward smaller, thriftier motoring just in time for the 1973 oil crisis.

Now? Britain’s car industry still exists, but mostly as an assembly annex for global players; Jaguar Land Rover (Indian-owned), Mini (German), Nissan (Japanese). There’s no national champion, no coherent industrial policy, and certainly no answer to what’s happening in 2025.

If the Japanese invasion of the Seventies was a creeping tide, China’s EV offensive is a tsunami and it’s already at the top of the high street.

Brands like BYD aren’t interested in mimicking Europe. They’re not building cut-price Golfs or knock-off 3 Series. They’re building next-generation tech ecosystems, cars integrated with their own batteries, software, semiconductors and AI platforms. Vertical integration gives them control over cost, quality, and pace that would’ve made Soichiro Honda weep with envy.

MG, once the darling of leafy Home Counties motoring is now a Chinese spearhead, its ZS EV undercutting legacy rivals by thousands while offering more kit, more range and fewer reasons to say no. Omoda and Jaecoo, still unfamiliar to British tongues, are bringing cars that wouldn’t look out of place in a Mercedes showroom but cost the same as a base Focus.

Unlike the Japanese back in the day, these newcomers don’t need to earn trust through decades of reliability reports and mechanically sound mediocrity. They’ve entered a market that wants disruption. Today’s car buyer shops online, trusts tech reviews more than showroom patter, and is more concerned with charging speed and infotainment updates than whether the badge has a Le Mans win.

The Seventies were no picnic; oil shocks, inflation, a government more concerned with surviving until Thursday than with industrial strategy. But crucially, consumers shifted toward Japanese imports because of price and economy. The Datsun 120Y, the darling of driving school cars, wasn’t just cheaper, it went further on a gallon, didn’t need fettling every weekend, and looked vaguely modern compared to a Maxi.

Today, the driver isn’t petrol prices, it’s policy. The UK’s net-zero mandate has lit a fire under EV adoption, and with the 2030 ICE ban looming, demand is being turbocharged not by market whim, but by regulation.

The Chinese have timed it to perfection. While European and Japanese marques scramble to electrify ICE platforms and untangle semiconductor bottlenecks, Chinese firms are shipping fully electric, ground-up platforms by the boatload. And they’re doing it without the millstone of legacy dealerships or brand baggage.

The UK, still licking its post-Brexit wounds, has kept tariffs off the table. Although just this week has excluded Chinese EV from the £3750 EV Subsidy redux. Unlike the EU, which has slapped Chinese EVs with duties up to 45% and minimum pricing, Britain remains wide open. The logic? Lower prices accelerate EV adoption. There’s no domestic champion to shield, and Downing Street would rather see a car plant in Swindon even if it flies a red star than an empty field.

In the Seventies, faced with growing Japanese dominance, the UK government tried the polite approach: voluntary export restraints, 20% tariffs, and veiled threats in Hansard. It didn’t work and by the time ministers finished their brandy, Nissan was already laying foundations in Sunderland.

This time, we’re not even pretending to resist. Open markets, loose regulation, and generous tax incentives make the UK a Chinese dream. While Brussels rattles sabres, Whitehall rolls out the red carpet.

Strategically, it’s a gamble. We’re hoping that in return for market access, Chinese brands will localise production, build battery plants, and create jobs. It’s industrial policy by osmosis. If it works, we’ll get investment without picking winners. If it doesn’t, we’ll be left with a forecourt full of imports and no local stake in the future of motoring.

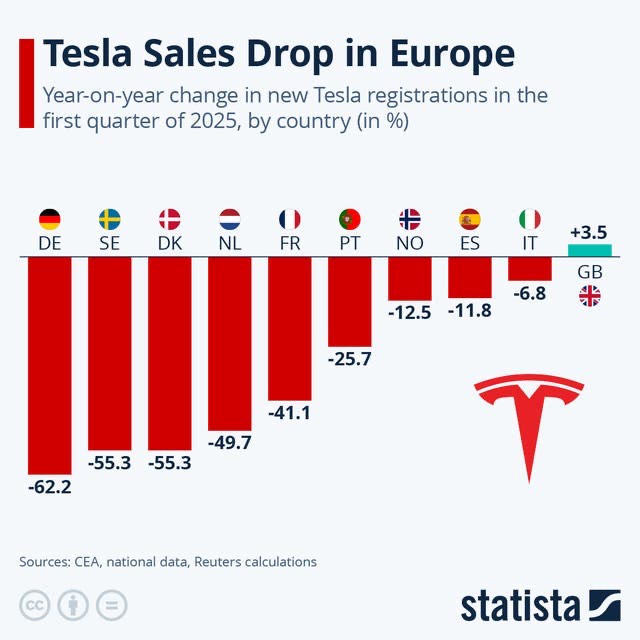

Let’s put it in context. Japanese brands took a decade to crack the UK market. Chinese brands have done it in less than five years. BYD sells more EVs than Volkswagen globally. Their battery division, CATL, probably supplies half the industry. This isn’t incremental progress it’s industrial domination.

Technologically, the difference is night and day. Japan gave us better-built Escorts. China is giving us cars that update over-the-air, offer Level 2 autonomy, and come with smartphone apps that track your tyre pressure from Tenerife, they’re also safe with the top 5 Star NCAP safety rating. The EV isn’t just a new drivetrain – it’s a software platform, and China with 1.5 Billion inhabitants to test new tech on is miles ahead on that front. They can launch in foreign markets with proven new tech.

British car buyers in the 1970s were brand-loyal, suspicious of imports, and only changed their tune after being burned too many times by dodgy electricals and engines that were engineered to throw con-rods for fun at sixty five thousand miles (cough Ford). Today’s buyers are patently open to new brands and don’t care where a car is built – they care if it syncs with Spotify and charges in under 30 minutes.

Younger buyers, the key demographic for EVs, have no nostalgic attachment to Ford or Vauxhall. They trust influencers more than dealers. They’re digital natives in a world where Tesla has already redefined what a car can be and how it’s sold. Chinese brands, with their TikTok-savvy launches and online sales funnels, get this. The legacy players mostly don’t.

Will Chinese EVs kill off what remains of the British car industry? Unlikely, it’s already on life support. But they will dictate the pace, the technology, and the price point of Britain’s motoring future. That, more than anything, is the lesson we should have learned in the Seventies.

Then, we tried to shield British brands behind tariffs and pride. Now, we’ve flung the gates open and invited the dragon to dinner.

POSTSCRIPT:

In the Eighties, the Japanese built factories here. They hired local. They became part of the landscape. The Chinese? That’s still up in the air. The smart money says we’ll see BYD or Chery setting up UK operations soon – if not for patriotism, then for EU access via a tariff-free back door.

And when they do, remember this: we weren’t conquered. We just let them in. Smiling, silent, and WiFi-enabled – and that, is another story.